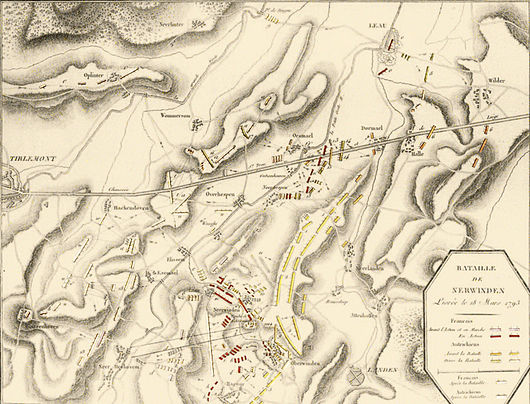

In the misty fields of eastern Belgium, around 40,000 Frenchmen squared off against around 40,000 Austrians in and around the small village of Neerwinden. This confrontation on the 18th of March in 1793 would be crucial to the future course of the First French Republic. It would be known as the Battle of Neerwinden.

General Charles Dumouriez would lead the French Revolutionary Army into battle. The lower estimates for Dumouriez’s forces were 40,000 foot infantry as well as 4,500 cavalry.1 His opposite number was the Prince of Coburg – Frederick Josias, and is credited with 30,000 foot infantry with 9,000 cavalry by Phipps.2

The French advanced sweeping up the settlements of Racour and Oberwinden, and then Neerwinden. Dumouriez planned to strike the Prince Josias’ left flank, believing that his right flank would be strongest in order to defend a potential cut off from coalition communications behind them. Austrian cavalry manoeuvres in the fields between the settlements were very effective, and fierce fighting ensued within the settlements. After being captured by each side a number of times, the Austrians seized Racour and Oberwinden, as well as Neerwinden, before driving the French further back with a cavalry charge. Dumouriez attempted another attack with his right flank, but this along with other French resistance withered away.3 In the morning, Dumouriez ordered a general French retreat from Neerwinden. 4

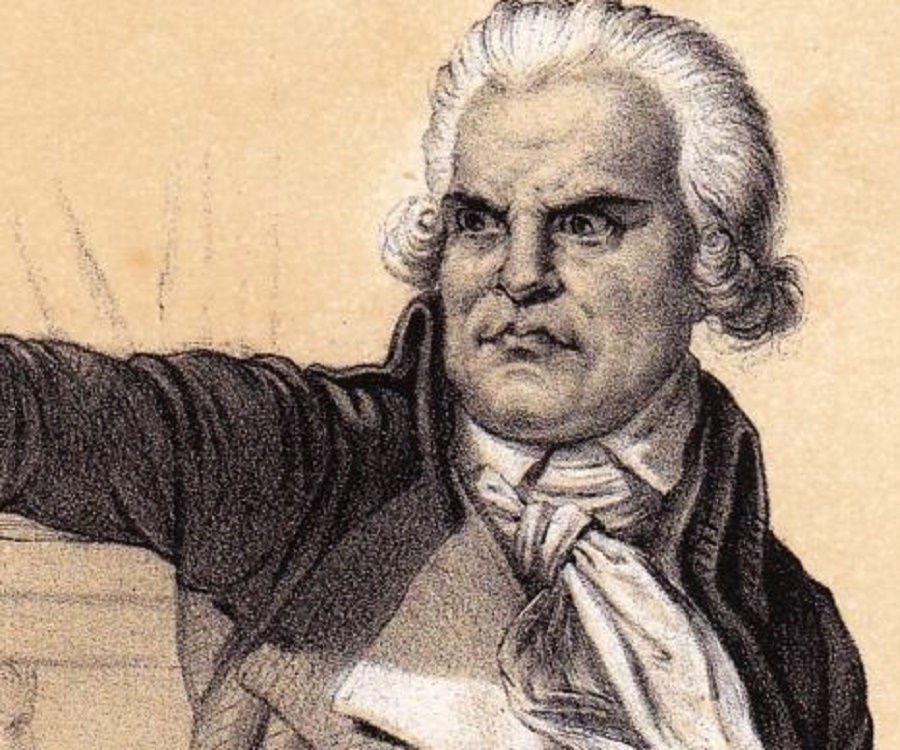

With the defeat at Neerwinden, Dumouriez was in a dire situation. He had been under criticism from the Jacobins, and four members of the National Convention had been dispatched to oversee his efforts. What Dumouriez did next was, frankly, rash. He had the four deputies from the Convention arrested, as well as the Minister of War – Pierre de Beurnoville and the general handed them over to the coalition forces.

He tried to persuade his men to march with him to Paris, and published a letter saying that if the National Convention did not recognise his absolute leadership, he would force them to. The army refused, and he ran off and defected to the Austrians.

And that was the end of Dumouriez’s story, as far as we’re concerned. He settled in England, and died in Henley-upon-Thames in 1823. But nonetheless he would leave his mark on history as his actions after the Battle of Neerwinden helped shape the future of the First French Republic. Dumouriez was linked with the Girondins, and the war had again turned against France, now on the back foot in the north, and the republic was under threat from its external enemies. But the republic was under threat internally too. The March 1793 Levy caused an uprising in the Vendee – parts of southern France. The central government described these rebels as royalist counter-revolutionaries, although the reality of the situation shows more characteristics of a rebellion of discontent than a rebellion to restore the Bourbons. The peasants in the Vendee were paying more in land tax than they had been paying before the revolution, and the wider economic situation was collapsing. By the end of the winter of 1792-93 grain prices had doubled, and the value of the assignat had halved. Large amounts of the currency (the assingnat) were still being pumped into the economy, against the demands of Saint-Just, which only worsened the economy

“The farmer does not want to save paper money and for this reason he is most reluctant to sell his grain.”5

The sale of Church land was also deeply unpopular among the population of the Vendee, as the land was generally bought by the bourgeoisie who raised the rents in these lands.6 The peasants who rebelled ‘looked to the nobles as their natural leaders.’7 The rebellion became so severe that 30,000 soldiers were drawn from the war front to put down the rebellion, but it would be deeply unsuccessful. The war in the Vendee would continue until 1796.

The coalition approach across the Rhine, the loss at Neerwinden, Dumouriez’s defection and the Vendee rebellion saw the young Republic under dire threat. The leadership sought to take decisive action.

President of the National Convention (Presidents were elected for two-week terms) Maxmin Isnard proposed the creation of a Committee of Public Safety – a nine-member executive group to the National Convention. Critically, the measure was endorsed by Danton, who would be instrumental in forming the first version of the CPS. The first CPS would even become known as ‘the Danton committee’.8 Danton was the most powerful member of the CPS, which included four other Montagnards, two Girondins and two members of the Plain. From its formation the CPS was tasked with supervising and speeding up the activity of ministers. The CPS’s powers were confirmed every month, however, by the National Convention.

The reason for the CPS having a Montagnard majority is the declining influence of the Girondin section of the Jacobin club. After the campaign for war and the trial of the King, they had lost support and suspicion arose about them being traitors to the republic. Dumouriez’s treachery only seemed to confirm to the republicans that they were facing enemies from within, and this feeling was furthered when the extent of the Vendee Rebellion was realised in late March of 1793. As the CPS formed under Danton’s leadership, the Girondin-Montagnard clash would come to a head with the republic entering its first spring.

On the 5th of April, the Jacobins sent out a letter to many of the societies across the country. The letter called for a dismissal of the deputies who had voted to pose the trial of the King to a popular vote, rather than the trial being decided by the National Convention. This had been demanded by the sans-culottes already, but now was seemingly the stance of the head of the Jacobin club. At the time, Jean-Paul Marat was the president of the Jacobins, and had signed the letter. Marat had reacted badly to the loss at Neerwinden, and he would have understood that this letter targeted the Girondins in particular. The letter was sent out some three weeks after Dumouriez’s betrayal, and it was especially alarming for those many deputies who had voted for a popular vote on the King’s life. 8 days later, a Girondin deputy decided to take action. The downward slide for his faction had gone on long enough, and with a speech in the Convention, Marguerite Guadet declared that Marat should be arrested for his signing of the letter which threatened the legitimacy of the Convention itself. The measure was passed by 226 votes to 93. 9

Marat was incredibly popular with the sans-culottes, and his supporters gathered near the Revolutionary Tribunal – a tribunal set up to try those suspected of counter-revolutionary activity. The tribunal itself would go on to be a key mechanism in the Terror, condemning suspects to death in many cases. Danton defended the setting up of the tribunal:

“Let us be terrible so that the people will not have to be.”10

In court Marat portrayed himself as a champion of the people, and that the revolution belonged to them, not the Girondins. He claimed he was ‘the apostle and martyr of liberty’. Marat was finally acquitted on the 24th of April, to the jubilation of his followers. A move from the Girondins to take out one of the most influential Montagnards had failed, but they would turn their attacks to the Paris Commune, the birthplace of the Jacobins and the centre of Montagnard power. On the 17th of May Guadet denounced the Paris Commune describing it as “authorities devoted to anarchy” and “political domination”. 11 Guadet declared that the Commune had to be destroyed, and twelve deputies were tasked with its dismantlement – all Girondin – called the Commission of Twelve. The Commission called for Hebert to be arrested on the 24th of May, and in response on the 25th, the Commune demanded that arrested ‘patriots’, including Hebert, be released. Isnard, the man who first proposed the creation of the CPS retorted in extraordinary fashion:

“If any attack made on persons representative of the nation, then I declare to you in the name of the whole country that Paris would be destroyed; soon people would be searching along the banks of the Seine to find out whether Paris ever existed.”

The next day, on the 26th, Robespierre called on the people to revolt. The sans-culottes rallied. The contesting factions were pushing each other to the brink, to see who blinks first. From the 31st of May to the 2nd of June, the Girondins and Montagnards would clash for the last time.

An insurrection began on the 31st, and revolutionary delegates from the 33 sections of Paris reinstated the powers of the Commune at around 6:00 am. They told the commune that they were to speak to Francois Hanriot, a battlement commander, and make him the commander of the Paris National Guard. The city gates were closed and the Convention was called to assemble. Brissot and Danton, accompanied by Guadet, Isnard, and Saint-Just made their way to the Convention to observe the demands of the Paris Commune. The demands included the formation of a central revolutionary army, fixing the price of bread, and armouries created for the sans-culottes. Robespierre arrived, and made a speech denouncing and calling for the suppression of the Commission of Twelve. Vergniaud, a Girondin deputy, thought his speech had gone on long enough. He called out for Robespierre to get it over with, to which Robespierre responded:

“Yes, I will conclude, but it will be against you! Against you, who…wanted to send those responsible for it to the scaffold; against you, who have never ceased to incite to the destruction of Paris; against you, who wanted to save the tyrant; against you, who conspired with Dumouriez…”12

The Convention agreed to the suppression of the Commission of twelve by the end of the day, but the Commune was not yet satisfied.

The 2nd of June would see the end of the power struggle between the Girondins and Montagnards. The National Guard was still mobilised, and the day before Marat made a return to the Hotel de Ville and called for an assembly. The Commune was to deliver a petition calling for the arrest of the 22 at 18:00, but the Convention dispersed. The tocsin sounded again and the petition was to be given to the CPS to be deliberated over, and a response was to be given within three days.13

Despite this, the next day, a Sunday, Hanriot and his National Guard surrounded the Convention, with a force of 80,000 Frenchmen in arms.14 The session ensuing was bitter. Lanjuinais, a Girondin deputy, and exclaimed in fury at what was, in his opinion, treachery by the Paris Commune. His speech was met with shouting from across the Convention, that he wants a civil war, or a counter-revolution, and that he was insulting the people. His voice rose. Lanjuinais told the Convention that Paris was being oppressed by the Commune, and violence erupted. Various Montagnards raced over to him to rip him down from the tribune, where deputies spoke in the Convention. He held on to the tribune as he was being attacked and continued his speech:

“I demand the dissolution of all the revolutionist authorities in Paris. I demand that all they have done in the last three days be declared null.”15

The Commune’s petitioners rushed in, and called for Lanjuinais’ arrest, as well as the twenty-two Girondins for counter-revolutionary rhetoric and activity. It was ruled that the petition was to be decided upon by the CPS. 16

The petitioners stormed out of the Convention, straight to the National Guard. Orders were given to Hanriot that no deputy would be allowed to enter or exit the Convention. While the Girondins were being urged to give up their powers (Isnard, the president of the Convention for two weeks prior did so quickly), Lacroix, a Montagnard deputy came racing into the chamber calling out that he had been ‘insulted’ at the door, and that no-one was allowed to leave. Even Danton said that such a violation of the Convention should be avenged, but the Girondins remained under dire threat. Barrere of the Plain roused the deputies of the Convention to ‘cause the bayonets that surround you to be lowered’, meaning to confront the National Guard.17 Led by the president, Herault, the Convention marched to the exit. And there, at the door, they were greeted by none other than the commander of the National Guard – Hanriot. He looked to the head of the crowd – Herault, who told the commander, not fully grasping the gravity of the situation, that the Convention intended to promote the people’s happiness, asking ‘what do the people require?’18

Hanriot, holding his cannon, spoke to the deputies around Herault.

“Tell your stupid president that he and his assembly are fucked, and that if within one hour he doesn’t deliver to me the Twenty-two, I’m going to blast it to the ground.”19

Time had run out for the Girondins. The Assembly were prevented from leaving at every exit from the Convention, and they proceeded to vote for the arrest of twenty-nine Girondin deputies. Among these included Brissot, Guadet, Vergniaud, and Lanjuinais.

Many more Girondins would be proscribed, and the original Twenty-two were tried in the Revolutionary Tribunal beginning on the 24th of October. Lanjuinais managed to escape before this but the Twenty-two were condemned to be executed on the 31st. It took 36 minutes to execute them.20 On the way to their execution they all sang La Marseillaise, and continued as they were executed.21 Vergniaud was the last.22 Marie Phillipon was imprisoned and later executed on the 8th of November. Jean Roland, her husband, upon learning of her fate in Paris, sat down beside a tree, and wrote out a short note:

“From the moment when I learned that they had murdered my wife, I would no longer remain in a world stained with enemies.”

Jean proceeded to sink a knife into his chest.

The Girondins were totally removed from the Convention, leaving the government dominated by the Montagnards, and the CPS led by Danton.

Jean-Paul Marat retired. He had been suffering badly from a worsening skin condition, akin to severe eczema. To remedy this, he often bathed in oatmeal, and would do his work on a table above his tub. Despite this he would still carry out official business, sending letters to the Convention, and corresponding with Robespierre and Danton, although they began to distance themselves from the now retired Marat. On the 13th of July, a young woman with brown hair and dark eyes by the name of Charlotte Corday came to Marat’s home with vital information regarding escaped Girondins following the proscriptions in June. Marat’s wife advised against speaking to Corday, but he did so anyway. They spoke for around fifteen minutes, as Corday listed the names of deputies and explained what was happening in Normandy – where the Girondins had escaped to. Corday claimed that Marat said to her “Their heads will fall within a fortnight.”

Then, the twenty-four year old Corday stood up, brandished a knife from her corset, and drove it into Marat’s heart.23

The blood loss was massive. Marat cried out “Help me, my dear friend!” to his wife, and slumped to his death.

Corday was promptly executed four days later, saying that she had killed one man ‘to save 100,000’. Marat died in the vain belief of Corday’s that it would bring the Reign of Terror to an end. Rather, it was with the fall of the Girondins that the Terror began to accelerate. The insurrection of the 31st of May to the 2nd of June saw a clear dominance by one faction for the first time.

Marat’s death would be immortalised by David, in his painting aptly titled – The Death of Marat. It shows him dead in his bathtub, in a position similar to a traditional position in which Jesus is portrayed. Marat was not the Jesus of the French Revolution, but his death became one of Montagnard tragedy. His paper The People’s Friend was published for the last time on the 14th of July, and he would become glorified by the Montagnards. Nonetheless his assassination was both a signpost of what the rule of the National Convention had been so far, and what it was to become.

Up until the fall of the Girondins the French Revolution had been a struggle of one ideal against another – at first Royalism vs. Constitutional Monarchism, then Constitutional Monarchism vs. Republicanism. When the struggle of Girondinism and Montagnardism ended – there was no opposition to take the place of the Girondins.

This unrestricted rule combined with the political extremism of the Montagnards would see the Terror become its most terrible, as the CPS came into its position of dominance. Though with the Girondins gone, the Republic was still under dire threat. On the morning of the 2nd of June it was announced in the Convention that in Lyon, Vendee Rebels had seized the local assembly, and some 800 republicans died. The Vendee Rebellion threatened the very existence of the republic as did the approaching coalition in the east. Danton, Robespierre and Saint-Just were tasked with leading the Montagnards, and thus the republic, into the most critical phase of the revolution.

1 Ramsey Phipps, The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshalls under Napoleon I, 2011, p. 155

2 Ibid

3 Rickard, J (12 January 2009), Battle of Neerwinden, 18 March 1793 , http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_neerwinden_1793.html

4 Theodore Dodge, Napoleon: A History of the Art of War: From the Beginning of the French Revolution, P. 103

5 Access to History: France in Revolution P. 95

6 Ibid

7 Ibid

8 Hillary Mantel, 2009, He Roared, London Review of Books. 3 (15): 3–6

9 Albert Sobul, The French Revolution: 1787-1799, 1974, P. 307

10 Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, Simon Schama, P. 706

11 Albert Soubul, The French Revolution: 1787-1799, P. 309

12 Albert Mathiez, The French Revolution, 1929, P. 324

13 The French Revolution, a Political History, 1789-1804, in 4 vols. Vol. III, François-Alphonse, 1910

14 Access to History: France in Revolution

15 Francois Mignet, History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814, 1824, P. 297

16 Ibid

17 Ibid P. 298

18 Ibid

19 David Bell, When Terror Was Young, https://jshare.johnshopkins.edu/myweb/davidbell/andress.pdf

20 Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, 1989, P. 803-805

21 William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 1989, P. 289

22 http://www.executedtoday.com/2008/10/31/1793-girondins-girondists-pierre-vergniaud/

23 Well, not quite his heart, very close to it though, and it did cause severe blood loss very quickly