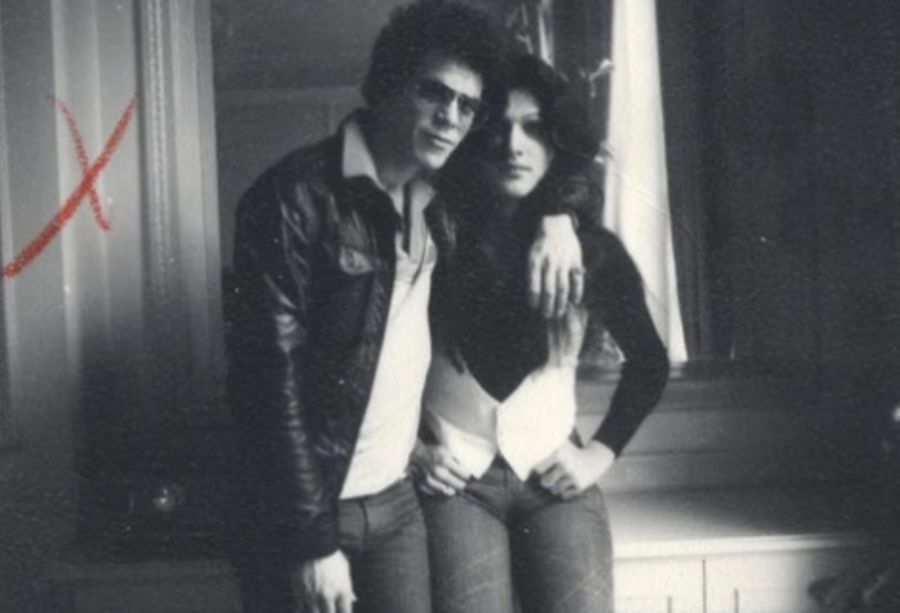

“It was in a late night club in Greenwich Village. I’d been up for days as usual and everything was at that super-real, glowing stage. I walked in there and there was this amazing person, this incredible head, kind of vibrating out of it all. Rachel was wearing this amazing make-up and dress and was obviously in a different world to anyone else in the place. Eventually I spoke and she came home with me. I rapped for hours and hours, while Rachel just sat there looking at me saying nothing. At the time I was living with a girl, a crazy blonde lady and I kind of wanted us all three to live together but somehow it was too heavy for her. Rachel just stayed on and the girl moved out. Rachel was completely disinterested in who I was and what I did. Nothing could impress her. He’d hardly heard my music and didn’t like it all that much when he did.

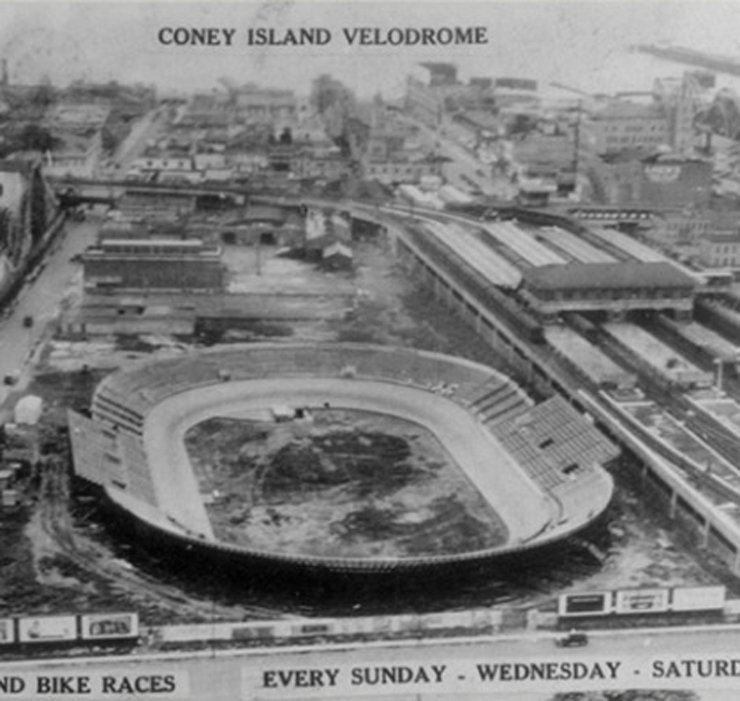

At the velodrome on Coney Island in the late 1920s, Babe Ruth stood at the start/finish line, starter pistol in hand. His shot would start a sprint race where Ray Eaton of East Orange, New Jersey set the best time in two out of three heats, and won the race.

Eaton had travelled from New Jersey to New York, all the way along to Coney Island, as his ancestors had before him, where the island’s simultaneous proximity and perceived distance from the city had made it a popular destination for the wealthy families of Brooklyn chasing an afternoon of sunshine. In the 19th Century transport links to the island gradually improved – first there was a road, then a steamship service. The introduction of a ferry line and railroad in the 1870s led to an increase of middle class visitors to the island, which was quickly taking on its role as a domestic holiday favourite. The island began to take on a distinct seaside character which propelled its popularity and success even further. By the beginning of the 20th century, the island had embraced its role as a getaway, and two new huge amusement parks were opened – Luna Park, and Dreamland – each complete with rollercoasters, railway rides, and electric light shows. In the first half of the century the island even embraced bicycle racing, with the construction of the Coney Island Velodrome, hosting races until its demolition in 1950.

Some forty odd years after Mr Eaton won that famous race which Mr Ruth had the honour of starting, far away on the other side of New York, Lou Reed encountered a dazzling figure across a smoky bar. Her name was Rachel Humphreys. Reed had been reeling from the commercial and critical failure of his now heralded 1973 LP Berlin, and quickly fell under Rachel’s spell. Humphreys was transgender. She spoke about how she hated her penis, and eventually sought out gender reassignment surgery. She became his muse.

By the 1970s Coney Island was suffering. The city had been tied up in legal disputes with Fred Trump and Norman Kaufman, and attendance had fallen across the board. The perception of Coney Island was one of deterioration – dilapidated amusement parks and abandoned boardwalks. Social issues became more problematic in the area as well, with crime increasing and a drug epidemic gripping the community. When the papers came to visit the the mood had turned from the carefree environment of the 1920s, saying the ‘grand old dame of amusement parks’ was grand no more. After generations of development, Coney Island went from being a place of hope and promise to one whose primary characteristic was of general decline. In the 90s the island underwent something of a minor revival, with a successful rebuilding of the fairground Steeplechase Park in the model of the original parks, and an unsuccessful ‘Sportsplex’, planned to be constructed in tandem with a social housing initiative. Some of the islands rollercoasters were even designated as official city landmarks.

There was too, in the 90s, a significant cultural bone thrown to the days gone by of Coney Island, when Homer, Apu, Wiggum, and Skinners performed ‘Goodbye, My Coney Island Baby’ in the barbershop quartet episode of The Simpsons, a recollection of Homer’s band the Be Sharps, and their Beatles-like rise and fall. Composed by Les Applegate back in the 20s, the high tempo and traditional structure harkens back to a time of prosperity for the island, and it’s this memory that the island still holds within its culture today. It followed the trajectory of so many seaside resorts which experienced early inspiration and hope, only to taper off, like Blackpool, though another English allusion to Brighton may appear to be more obvious, with locations in and around Coney Island being named after the British seaside town. The earliest fathers of Coney Island wanted to carry this character with them, but Brighton has flourished, unlike the decline experienced by its brethren.

Yet the character of the island stretches far beyond those traditionally known as the founders of Coney Island. In fact the island had an entirely different culture and character prior to the arrival of European settlers, who quickly transformed the eastern seaboard of America into something more tasteful to their old world sensibilities.

Anthony Jansen Van Salee became the first grantee of land on Coney Island in 1645 – a New Netherlands settler part of the mighty Vanderbilt lineage. This came after the settlers of New Amsterdam ‘purchased’ much of modern day southern Brooklyn – from Gerritsen Creek up to Coney Island – from the native inhabitants. Treaties were drawn up and signed with great haste so as not to inhibit the paths of New Netherlands settlers who had made their journeys and sought some reward for it. The exchange of land was made in return for goods – a blanket, a gun, and a kettle were included in the ‘purchase’ for this massive tract of land. The Dutch population grew and the native population shrank.

The seizure of land and ensuing westward expansion formed part of a mythic cultural moment of manifest destiny, underlined by military campaigns of huge bloodshed and destruction. By virtue of its history, Coney Island’s anglocentric origins are that of stolen land. In sharp contrast to its commercial and cultural purpose of relaxation and leisure, the accumulated character of the island is complicated. This island cum peninsula though had no agency, through no choice of its own it changed in ownership and cultural significance and will continue to do so without say. The island inherited its contradictions.

“All the albums I put out after this are going to be things I want to put out. No more bullshit, no more dyed hair, faggot junkie trip. I mimic me better than anyone else, so if everybody else is making money ripping me off, I figure maybe I better get in on it. Why not? I created Lou Reed. I have nothing even faintly in common with that guy but I can play him well—- really well.”

Reed had an intrinsic self-awareness throughout his work and by the 1980s had seemingly made peace with his image and artistic nature. While Reed had somewhat of an active part in the creation of his image and his ultimate outward expression of it – his art, he despises those who capitalise upon it, and is seemingly disconnected to where his art originally came from. The idea of someone playing the character of themselves isn’t necessarily a new one, but the associated dysphoria that comes with this carries a heavy mental toll.

Reed had a particular way of expressing these ideas and conflicts from his mind as a remarkably talented songwriter. The opening track of The Velvet Underground’s self-titled third album, Candy Says, begins with a gentle trickle of electric guitar, and goes into a stripped down, tender affair. A tribute to Candy Darling, a Factory-era Warhol icon whose appearances in his films Flesh and Women earned her cult status, the same Candy referred to in the second verse of Reed’s biggest hit – Walk on the Wild Side. Sung by Doug Yule (replacement to founding member John Cale) from Darling’s perspective, it opens with lines lamenting her distaste for the body that she lives with. Reed’s words are raw and challenging, and portrayed a very real empathy and understanding.

Some ten years later, Reed and Rachel Humphreys split up, reportedly because Humphreys wanted to proceed with gender reassignment surgery. Reed never mentioned her again.

There is precious little known about their relationship and after they split, the Rachel Humphreys trail goes cold until she died in 1990 during the AIDS epidemic. It speaks to the lack of historical agency belonging to the trans community, that once their relationship with the cis rock star concludes, their narrative ends, and the rock star’s goes on.

Reed seemingly didn’t respect Humphreys’ pronouns either, at least according to Andy Warhol, who said he called Rachel “she, because she’s always in drag, but then Lou calls him ‘he'”. It speaks to an extraordinary lack of care and understanding for his partner, and seems so utterly at odds with the compassion and tragic beauty of Candy Says.

Candy says…

I’ve come to hate my body

And all that it requires

In this world

But let’s take a step back for a minute, because before we go speaking about the nuances of a relationship between two people about whom precious little is known, we should recognise that all the quotes in the world won’t reveal the truth about the intricacies of any relationship, let alone that of someone as complicated as Lou Reed. Rachel Humphreys though remains absent from the records, and will likely never have her half of the painting coloured in.

Humphreys may have, at times, found herself playing a character of sorts. Whether it be playing a drag queen, or playing herself as a boy or playing herself as a girl. She, unlike Reed, had no agency over her dysphoria. She was born into it.

But for a few fleeting moments, Humphreys was Reed’s muse, and Reed was crazy about her. He wrote and dedicated his sixth album to her, and adapted an old poem of his ,The Coach and The Glory of Love, for the title track – Coney Island Baby. It clocks in at six and a half minutes, and consists of Lou’s patented spoken word style over romantic guitars and drums. He rambles on about love, football, and the city, and eventually signs off with “I’m a Coney Island baby now..”

It’s a simple remark that carries the weight of the world behind it. And perhaps it was a nod to a barbershop classic of days gone by, and maybe it’s somehow connected to the thread running through Coney Island’s complex and contradictory history that runs up to the modern day with President Biden and the Jonas Brothers jumping on the latest trend from the community. He goes on to dedicate the song to his old primary school in Brooklyn sending the message “From Lou and Rachel”.

For a brief period, the stars aligned and allowed this place and these people to share a moment in spite of the struggle that comes with their stories, which Reed captured in perfectly suspended animation.

I met somebody a few weeks ago who said something that resonated with me – “To be an artist is to be expected to produce.” While axioms like this are difficult to contend with, there is something there about the relation of the artist to the audience.

Human life is absurd and human brains are complicated and often contradictory, and in some ways art is an attempt to make sense of it all. As an audience, by offering some understanding to the context of artwork, we can make better sense of the pieces themselves and return some form of agency to the artist in a world that is increasingly dysphoric and confusing. It is an agency that Reed never afforded Humphreys, despite her own dysphoric and confusing world, but away from Reed she would at least have been able to take back some of her autonomy, out of the spotlight. Art can be an antithesis to tragedy but deserves our care and attention to be seen in its true light, qualities that are running desperately low these days.

“Saying ‘I’m a Coney Island baby’ at the end of that song is like saying I haven’t backed off an inch. And don’t you forget it.“