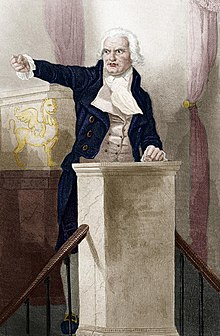

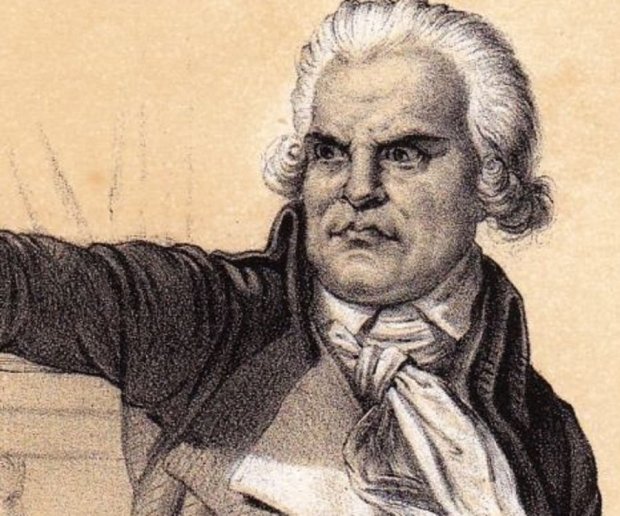

The Montagnards liked to talk about being daring. They seemed to portray themselves as warriors in the face of great adversity. In a way, they were. The revolt in the Vendee and the revolutionary war were crises enough alone, but together created a catastrophic threat on the republic. Danton remained a figure of defiance. The head of the CPS was moving the political game forward after the fall of the Girondins. The revolution had galvanised the French people, but by June of 1793, the internal rebellion was widely known. Nonetheless those who remained on the side of the revolutionaries were more than ready to fight their corner. The sans-culottes, particularly, would be influential in shaping the course of the coming political events. They were encouraged in their own defiance by their Montagnard leaders. One of Danton’s most enduring quotes would put the Montagnard position well – in the face of dire threat to the republic:

“We must dare, and dare again, and go on daring.”

Again Danton displays his excellent command over language. Despite his efforts, guiding the CPS through its earliest months and through the purge of the Girondins, the committee was recomposed on the 10th of July. Without Danton included. 1

Now, despite this, he continued to support the committee’s power, maintaining his line that the committee was a hand with which to grasp the power of the Revolutionary Tribunal. Danton never really achieved this whilst at the head of the CPS, but he would bear witness to a massive expansion of the CPS’ power where they would, very firmly, grasp the Revolutionary Tribunal.

The CPS was recomposed on the 10th, and it would include 11 members. Saint-Just was included, and he would become the leading spokesperson of the CPS. Of course, there were no more Girondins on the committee, but 9 of the 11 were Montagnards, including Saint-Just. Two deputies from the Plain were included – Bertrand Barere and Lazare Carnot. Other prominent members of the CPS include Couthon, Herbois and Sechelles.

Critically, on the 27th of July, a twelfth member would be elected to the Committee of Public Safety. He had not sought the position. It was Maximilien Robespierre.

Alongside his election, the CPS entered a position of even more power. They were to become active rulers of France, as the republic’s fleeting democracy appeared to evaporate in favour of a more powerful executive. The role of the CPS now included governance of the war effort. In July, the French were still on the back foot after Neerwinden, and had pulled thousands of troops from the front to deal with the Vendee crisis. France however did believe they could change the course of the war following Neerwinden, through a, perhaps, unforeseen ally.

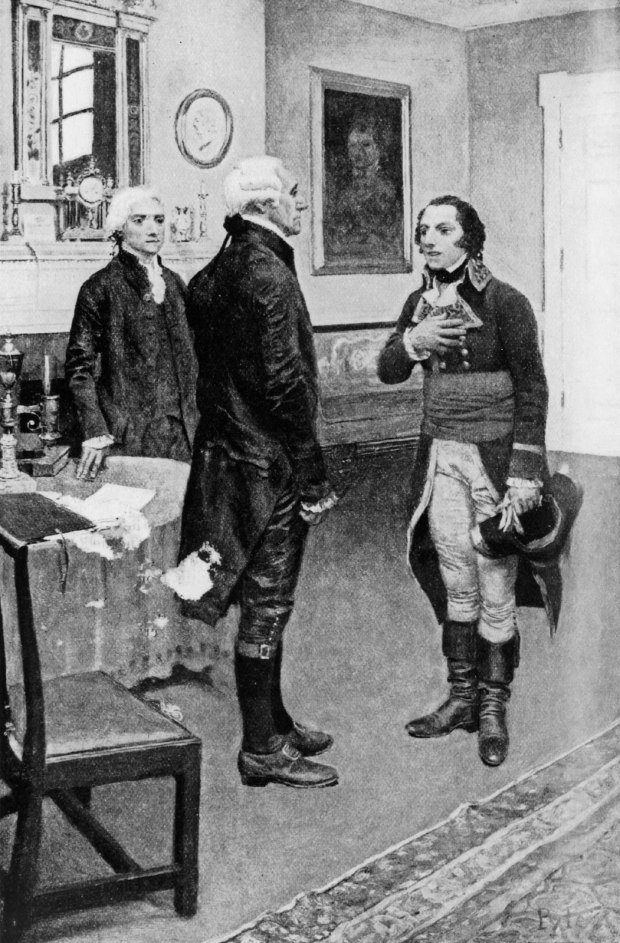

Edmond Charles-Genet was dispatched by France to the United States of America to curry support for the USA entering the war. The ambassador would become embroiled in what became known as the Citizen Genet affair. He landed in South Carolina on April the 8th, but instead of travelling to Philadelphia to present himself to President Washington he stayed in South Carolina recruiting American mercenaries, eventually commissioning four privateers – one of which was called the Sans-culottes. On the 22nd of April Washington made his Neutrality Proclamation, ruling the USA out of the War of the 1st Coalition. At last Genet met with Washington, and wanted to know why the US had declared its neutrality – president-to-be Thomas Jefferson said that Genet’s actions had been unacceptable. All the while, the American privateers were capturing British ships, and preparing to move against the Spanish.

Genet would go on defying the US government, even at one point receiving an 8,000-word letter complaining of his continued action in attacks on British ships. Washington eventually asked France to recall Genet. In January of 1794 the Jacobins quickly issued an arrest order, telling Genet to return to Paris. He was well aware of his likely fate if he returned to Paris – the guillotine. So he applied for asylum, and his biggest opponent in the cabinet – Alexander Hamilton – persuaded Washington into allowing him the asylum.

Nonetheless, Genet’s failures in the USA meant that the French remained on the back foot in the revolutionary war. The executive required strengthening, to sort out the chaos plaguing France. A new constitution would be drafted – largely by Saint-Just, which would become known as the Constitution of 1793 which included a new declaration of rights. This included the right to work and education, as well as the right of insurrection. Also all adult males were to have the vote.2

As said earlier, the CPS were in charge of the war effort, and were even to appoint generals. Not only this, the CPS was not in charge of appointing judges to the revolutionary tribunals, and perhaps most importantly – appoint juries to the revolutionary tribunals. The CPS could essentially fix the result of any trial they liked, and thousands of suspects would be executed. This CPS dominance over trials of suspects would be one of the reasons that the dictatorship of the CPS would be become known as The Terror.

With Robespierre now establishing himself on the Committee, on the 23rd of August, the Levee en Masse was decreed.

The Levee en Masse was a watershed moment in European history. For the first time an entire nation was mobilised – for the first time a nation existed in a state of total war. The decree stated the following:

“Until the enemies of France have been expelled from the territory of the Republic, all Frenchmen are in a state of permanent requisition from the army.”3

The decree saw a massive effort of mobilisation from France. Some 500,000 unmarried men were conscripted. State military factories were set up that produced ammunition. The Church was ransacked – church bells were melted down as well as religious ornaments like chalices. This was an unprecedented level of mobilisation, which would lead to a manner of warfare never seen in Europe, and would become the basis of some of the bloodiest warfare after this time period. When the invaders arrived, they met a people in arms.4

Despite this, the economy struggled to recover. The assignat’s value continued to fall, and when grain supplies were reduced by three quarters unrest began to brew in Paris. Jacques Roux, a priest, had begun to develop a following devout to his political rhetoric. He demanded the execution of grain hoarders, who had plagued the French economy by hoarding grain and selling it at high prices. Robespierre was incensed. Roux was threatening the authority of the Convention, and he wasn’t about to stand for it. Roux was arrested.

Despite this, Roux would eventually get what he wanted. After a crowd marched on the Convention on the 5th of September, the Convention agreed to the formation of groups that were essentially citizen militia. They were called Armee Revolutionaire, whose instruction was to guarantee the grain supplies of cities round up hoarders and deserters and establish “revolutionary justice”.5

The General Maximum was put in place as a limit to bread prices and other essential goods. The prices would later be raised, and even applied to wages, greatly upsetting the sans-culottes.6

The revolution would even be extended to the calendar. The republic was seen as a new dawn for France, and so it was suitable that a new calendar was to be set up, and that year should simply be Year I. The months were actually named with reference to the seasonal activites and weather. For example Frimaire (from frost) was from the 21st of November to the 20th of December, and Germinal (from germination) would go from 20th of March to the 20th of April.

After a break in fighting since Neerwinden, revolutionary war came to a head at Wattignies, under the leadership of one Lazare Carnot. I won’t be going in depth with this battle, but I will tell the basic story.

Since joining the CPS, Carnot studied the military problems facing the Republic. He presented a lot of reports to the CPS with regard to the military situation, with one report urging a hastening in the conscription of some 300,000 men. He was sent to the northern front, to help restore morale to the Revolutionary Army following the tactical defeat at Neerwinden. He reorganised the army and established better discipline.7 However when it comes to Wattignies, the histories over Carnot diverge. The Encyclopadae Britannica uses Carnot’s account that his decisions were crucial, although Phipps strongly disagrees claiming that it the order of Battle was textbook Jourdan – the other military commander.8

Carnot portrayed himself as a military hero, although his prior organisational skills cannot be denied according to Glover.9 So much so that he was bestowed with the title ‘organiser of victory’.10 The Battle of Wattignies saw a crucial French victory, which again saw a turn in the tide of the War of the First Coalition. By the end of 1793, France had seen success in the war but also success against internal rebellion. The army had supressed revolts in the Vendee, albeit brutally.

Peasants were shot and killed. Farms and crops were destroyed. Women were raped. Prisons were overpopulated. Thousands were killed without a trial. Official sources tell us that 8,700 were condemned to execution in the Vendee. This makes up more than half of the official statistics for executions during the Terror. Most of these people were peasants too – few were bourgeoisie.11 Rosin details some of the atrocities in Lyon in December of 1793, in a letter to the Convention.

“The guillotine and the firing squad did justice to more than four hundred rebels…The republic has need of a great example – the Rhone, reddened with blood, must carry to its banks and to the sea, the corpses of those cowards who murdered our brothers.”12

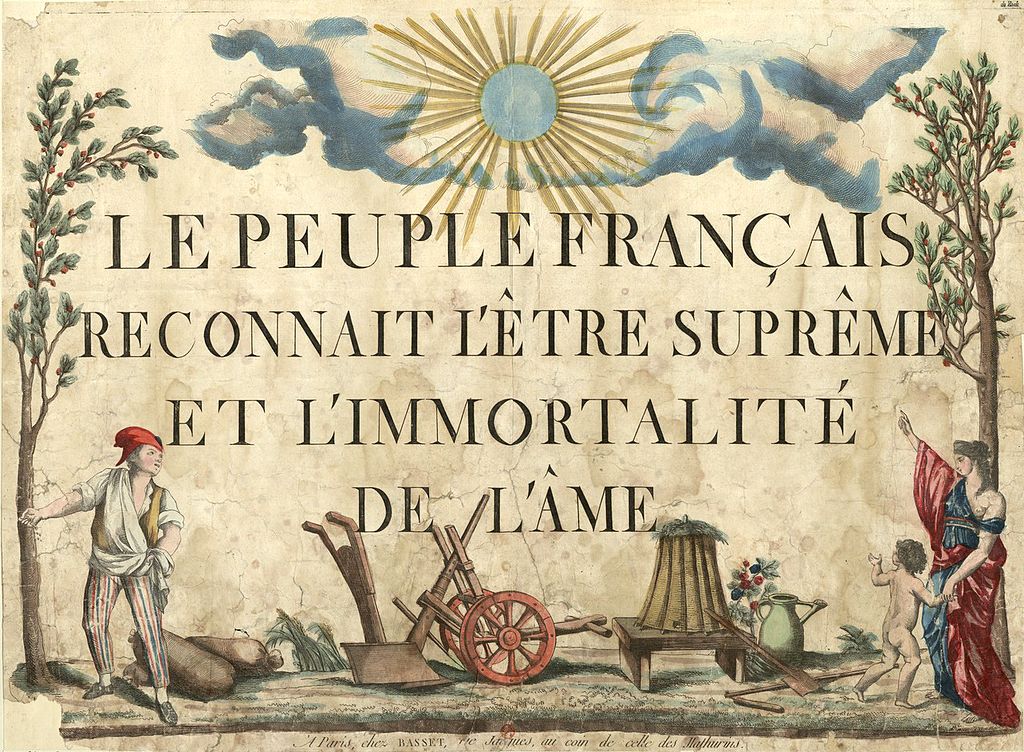

The terror even extended to religion, with an active dechristianisation effort from the CPS. With all these reforms, Robespierre had become the dominant member of the CPS, which essentially became his own dictatorship. He had his allies on the committee, most notably Saint-Just. Despite this the extent of the Terror had been going too far for some people.

Georges Danton had become deeply unhappy with Robespierre’s dominance, and he became Robespierre’s most notable rival. He had led the Republic through its rockiest period – during the purge of the Girondins. Nonetheless he found himself excluded from political proceedings as time went on. Yet he had become fabulously wealthy, which was highly suspicious, particularly after some 400,000 livres were unaccounted for in the Ministry of Justice. Danton began to attack the CPS, pushing to end the Terror and the centralisation imposed on France. He had also become anti-war, arguing it was responsible for the Terror. He enlisted the support of his friend Camille Desmoulins, who began publishing a newspaper – Le Vieux Cordelier in December highlighting these views. Danton’s support in the Convention made him a distinctive threat to the dictatorship of the CPS. Danton, once the most powerful figure in France was left grovelling in a cell, when he was arrested on the 30th of March 1794 for being suspected of plotting a coup.13

Georges Danton, along with Camille Desmoulins and many of their followers were executed on the 5th of April. His wife was executed days later.

These executions destroyed any dissent of the CPS. No-one spoke out. Criticism had been crushed under the CPS guillotine, and the CPS had a massive, seemingly unstoppable momentum. The CPS would reach its critical mass in The Great Terror.

In May, the government ordered the centralisation of Revolutionary Tribunals to Paris, in order to further control the proceedings of counter-revolutionary judgement. The Law of Prarial was passed, and it was, frankly, vague. Almost anyone could be arrested under this new law and no witnesses were to be called so as to speed up the process. Rather, judgments were to be made based on the conscience of the jurors. The defendants were not even allowed any counsel, and the only judgements were condemnation to death or acquittal. Robespierre did not care whether innocents were caught under his iron fist, so long as the enemies of the republic were crushed underneath. The Great Terror, which refers to the period from the 10th of June to the 27th of July, saw 1,594 people executed. The CPS was completely politically unopposed. Saint-Just said that “The Revolution is frozen.”14

Despite this, the CPS was gradually losing support, in an indiscreet fashion. Catholics had become deeply unhappy with Robespierre. His Cult of the Supreme Being was interpreted as being blasphemous. This Cult appeared to be Robespierre’s replacement for Christianity following the massive campaign of dechristianisation. Robespierre had also lost support from the sans-culottes, particularly due to the general maximum being applied to wages, as well as the end to direct democracy in the provinces. Lastly, Robespierre was losing support from his committees. Members of the CPS and Committee of General Security (CGS) had lost faith in Robespierre’s leadership. Billaud and Collot were upset with Robespierre’s persecution of an extreme left-wing leader – Hebert. Members were also suspicious of the Cult of Supreme Being, with Robespierre positioning himself to be the head priest of this new cult. This bubbling discontent underneath CPS rule surfaced in late July of 1794.15

Robespierre himself hadn’t made many public appearances since the beginning of the Great Terror, not attending CPS meetings or making any Convention speeches. He finally returned on the 26th of July, where he addressed the Convention, without notifying the CPS of what he was about to say.

Robespierre made a speech attacking members of the Convention and of the government, claiming that there were some individuals who were plotting against the rule of the CPS. His undoing was his refusal to name any of these alleged plotters. Moderates in the CPS like Barere and Carnot, who had come from the Plain and more extreme members like Collot and Fouche felt threatened, afraid of being arrested by Robespierre for plotting a coup, or counter-revolutionary activity. This paranoia instilled by Robespierre’s regime. On the 27th of July, Saint-Just was reading a report to the Convention, when he was interrupted by Jean Tallien, who denounced him and Robespierre’s tyranny. Billaud-Varenne, a member of the CPS joined the denounciation, and it goes that Saint-Just’s characteristic grace collapsed, and he failed to defend himself from the verbal onslaught. Robespierre jumped to his defence, pleading with the more right-wing parts of the Convention:

“Deputies of the right, men of honour, men of virtue, give me the floor, since the assassins will not.”16

Unfortunately for Robespierre, the right did not stir.17

A vote was taken to arrest Robespierre, Saint-Just, Hanriot (the commander of the National Guard – influential in the purge of the Girondins), Augustin (Robespierre’s brother) and Couthon.18

Despite this, they had to be taken to prisons controlled by the Paris Commune, which remained very much in support of Robespierre’s regime. The Paris Commune then ordered the mobilisation of the Sectional National Guard, and a showdown seemed likely between the Commune and the Convention. The Commune’s National Guard soldiers were being led by Coffinhal, and the Convention raised its own soldiers under the leadership of Barras. As Coffinahal’s soldiers approached the Convention and heard of the Convention raising its own army, confusion ensued, and organisation broke down. Hanriot eventually ordered the remaining soldiers back to the Hotel de Ville – Paris’ city hall. Robespierre and co gathered there.19

The Convention declared the group as outlaws, which meant they could be executed within 24 hours of arrest. The remaining Commune soldiers were thin, and through the later hours of the 27th of July, and the early hours of the 28th the last of the Commune’s soldiers deserted. At 2 AM on the 28th, Paul Barras and his force approached the undefended Hotel de Ville.20

As the Convention soldiers steamed through the city hall, the fugitives made various attempts to escape. Augustin jumped out of a window to escape, but broke his legs upon falling, and was arrested shortly after.21 Hanriot fell from a window and was found later in the day.22 Couthon was found lying at the bottom of a staircase.23 Saint-Just didn’t try to escape or hide, whilst Robespierre was shot in the jaw, either in trying to kill himself, or shot by a Convention soldier.24 The fugitives had been apprehended, and on the 28th of July, Robespierre, Saint-Just, Hanriot, Augustin and Couthon met the guillotine.

And with this, the Reign of Terror would come to an end, along with the story of the Jacobins, although they would remain relevant to pop up again in our story. Robespierre dominated for France for a little under a year, but met his demise when his support waned. Saint-Just died at the age of 26, with his promising, yet extremist, political career cut short.

Robespierre’s time was over, and he would go down in history as one of the key proponents of one of the most dramatic periods of the French Revolution. The republic went about licking its wounds, forming a new government and settling into a reactionary period of relative internal calm, with war brewing on the horizon.

1 Hillaire Belloc, Danton: A Study, 1899, P. 235

2 Access to History: France in Revolution, P. 110

3 Ibid

4 Ibid P. 111

5 Ibid

6 Ibid P. 113

7 Ibid, P. 94

8 Ramsey Phipps, The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshalls under Napoleon I, 2011, p. 259

9 Michael Glover, Jourdan: The True Patriot, 1987, P. 160

10 Dylan Rees, Access to History: France in Revoution, P.94

11 Ibid, P. 115-117

12 Ibid

13 Ibid P. 121-122

14 Ibid, P. 122-123

15 Ibid, P. 124-125

16 Peter Davis, The French Revolution: A Beginner’s Guide, 2012

17 Pierre-Toussaint Durand de Maillane, Histoire de la Convention Nationale, 198–201

18 Dylan Rees, France in Revolution, P. 125-127

19 John Merriman, A history of modern Europe: from the Renaissance to the present, p.507

20 Ibid

21 Ibid

22 Longman Group, Chronicle of the French Revolution, 1989, P.436

23 John Merriman, A history of modern Europe: from the Renaissance to the present, p.507

24 Ibid

25 Francois Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution, 1989